Iron and fertility: why iron is key for TTC and a healthy pregnancy

Iron deficiency is one of the most common nutrient gaps affecting those trying to conceive (TTC) and pregnant women. In Belgium and across Europe, iron deficiency and anaemia remain prevalent issues, especially for women of childbearing age. About 13–15% of Belgian women aged 15–49 have anaemia [1,2], and roughly 16% of pregnant women in Belgium develop anaemia [1].

Importantly, many more women have low iron stores even if their haemoglobin hasn’t fallen into the anaemic range. For example, a Belgian study found 19% of women of reproductive age had depleted iron stores (serum ferritin <15 μg/L) [3]. In pregnancy, iron deficiency becomes even more widespread. The same Belgian study found that in the first trimester, 6% of pregnant women had iron deficiency anaemia, and 23% of pregnant women in the third trimester [3].

In this article, we’ll look at:

Why iron is so important for fertility (for both natural conception and assisted reproduction) in women and men

Why iron needs rise dramatically during pregnancy

How to optimise iron status safely

How to boost iron intake with both animal and plant-based iron sources

Guidance on testing and supplementation.

The goal is to equip you with clear information to support your fertility journey and a healthy pregnancy.

What is iron?

Iron is an essential mineral that allows your body to transport oxygen, produce energy, and support cell growth. It is a key component of haemoglobin in red blood cells, which carries oxygen to your tissues, and it also plays a role in immune function, hormone production, and brain development. When iron levels are low, these systems become less efficient, which can affect energy, concentration, and the body’s ability to support fertility and pregnancy.

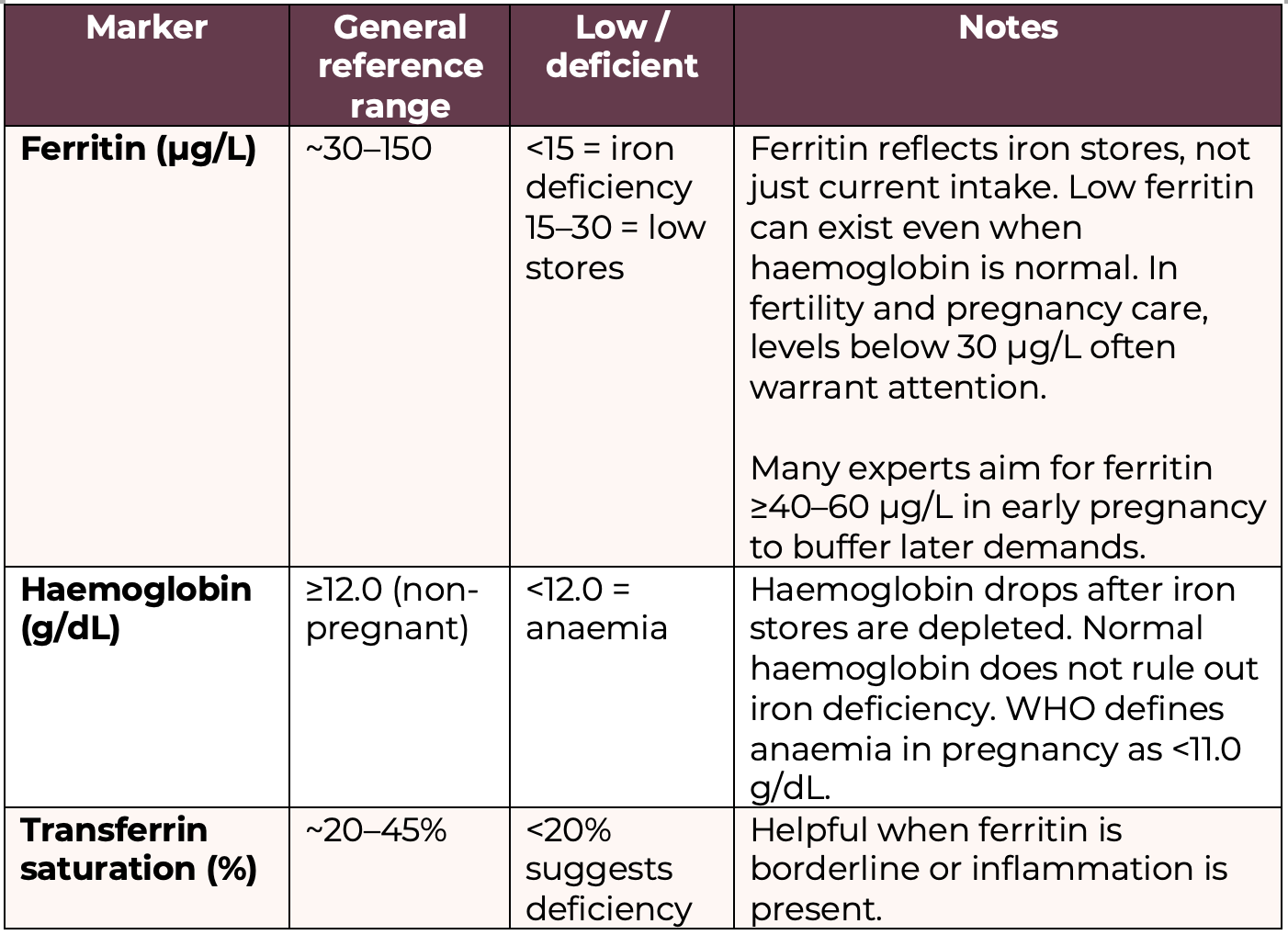

What is the difference between an iron deficiency and anaemia?

These terms are essentially referring to different levels of deficiency. Although for anaemia, other nutrients can also contribute to the condition, such as B12 and folate. You have the following level of iron status:

Iron replete: iron levels are good all-around

Iron depletion: starting to see a reduction of iron levels, generally reflected in the serum ferritin levels in the blood

Iron deficiency: deficiency is now clear, and you’ll see this reflected in serum ferritin, serum iron, and serum transferrin

Iron deficiency anaemia: all of the above, plus haemoglobin levels are also low

As you can see above, it’s critical to note that iron deficiency can exist without anaemia. In the early stages, the body draws down iron stores (measured by serum ferritin) before haemoglobin production is impacted. Many women have low ferritin (iron storage) but normal haemoglobin, which can still cause symptoms and may impair fertility and pregnancy outcomes. Fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath are common symptoms of iron deficiency.

In fact, research indicates that about 50% of pregnant women are not getting enough iron to meet pregnancy needs, and iron stores often decline as pregnancy progresses if no intervention is taken [4]. Even in healthy, non-anaemic women, ferritin levels can drop into the “deficient” range by the third trimester, as seen in the Irish study where >50% became iron-deficient without early supplementation [4].

Why iron matters for fertility (women and men)

Iron plays several essential roles in the body that directly impact fertility for both females and males:

Energy and oxygen transport

Iron is a core component of haemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. If iron levels are low, oxygen delivery to tissues suffers.

For someone trying to conceive, low energy and chronic fatigue can affect libido, mood, and overall wellbeing. Moreover, the uterus, ovaries, and other reproductive organs need a good oxygen supply to function optimally.

In men, adequate oxygenation of the testes is also important for sperm production. Thus, maintaining normal iron supports overall vitality and reproductive organ health.

Ovulation and egg quality

For women, iron appears to be linked to ovulation and egg development. Research suggests that women with iron deficiency are more likely to experience anovulation (lack of ovulation) or poor egg quality.

In one long-term study, women who took iron supplements had a 40% lower risk of ovulatory infertility (infertility due to failure to ovulate) compared to those who did not take supplements [5].

Low iron levels are associated with disruptions in menstrual cycles. In severe cases, iron deficiency can even lead to amenorrhea (absence of periods) as the body tries to conserve iron by stopping menstrual losses. By ensuring sufficient iron, you support regular ovulation and healthier eggs, which improves the chances of conception.

Implantation and early pregnancy

Iron is critical in the very early stages of pregnancy, often before a woman even knows she’s pregnant. After fertilization, the embryo must implant into the uterine lining and begin forming a placenta. This process requires rapidly dividing cells and increased blood supply, both of which depend on iron.

Iron is required for DNA synthesis and cell division, so a deficiency could impair the development of the placenta and embryo. Studies have linked iron deficiency to impaired placental development and a higher risk of early pregnancy loss [6].

Even without causing anaemia, low maternal iron can compromise the formation of a healthy placenta and limit oxygen delivery to the embryo, potentially affecting implantation success.

Sperm development

It’s not just women; men’s fertility can also be affected by iron status. Iron is needed for normal spermatogenesis (sperm production) in the testes [7]. Low iron in men may lead to lower sperm quality, including issues like reduced sperm count or motility [7].

On the other hand, too much iron can be harmful due to oxidative stress: excess iron (such as in men with genetic iron overload conditions) can increase oxidative damage to sperm and testicular tissue [7]. Thus, a balance is key.

For most men, iron deficiency is less common, but it can occur (for instance, in those with chronic illnesses, gastrointestinal disorders, or very restrictive diets). Ensuring men have sufficient iron (but not excessive) supports healthy sperm parameters and overall reproductive health.

In couples facing infertility, it’s worthwhile for men to have basic labs as well (including iron) especially if there are signs of deficiency, like unexplained fatigue or known nutritional issues.

Preventing early fatigue and loss of libido

Fatigue is one of the first signs of iron deficiency, even before anaemia is severe. In the context of fertility, constant fatigue can reduce interest in intimacy and make the process of trying to conceive more stressful or taxing.

Iron in pregnancy: increased needs and risks of deficiency

Once pregnancy is achieved, iron requirements climb significantly. In fact, by the second and third trimester, a woman’s body is working hard to expand its blood volume (by up to ~50%) to supply the growing fetus and placenta with oxygen and nutrients. Iron is a critical ingredient for making all that extra blood.

Let’s break down why iron demand is higher in pregnancy and what can happen if iron runs low:

Higher iron requirements

Essentially, pregnancy may nearly double the daily iron need. The body uses this iron to:

Build the baby’s blood supply

Support the placenta

Increase the mother’s red blood cell mass

Prepare for blood loss at delivery.

Iron deficiency and anaemia in pregnancy

If a pregnant woman’s iron intake or stores are insufficient to meet the above demands, she can become iron-deficient or anaemic quite quickly, even if she started pregnancy with decent levels.

Iron deficiency in pregnancy tends to worsen with each trimester if not addressed [4]. Early on, the body might compensate, but by mid-pregnancy many women develop low ferritin, and by the third trimester a large proportion may develop iron-deficiency anaemia.

Risks of untreated iron deficiency

Maternal iron deficiency and anaemia carry risks for both mother and baby.

For the mother:

Extreme fatigue, dizziness, headaches, and breathlessness

Higher risk for complications such as postpartum haemorrhage (excessive bleeding at birth) and infections

For the baby:

Higher chances of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small-for-gestational-age babies [4].

Potential long-term developmental impacts. For example, low maternal iron has been associated with poorer neurological development in the child, possibly due to inadequate iron during critical prenatal brain development [4].

Symptoms and Quality of Life

Beyond the clinical risks, being iron-deficient in pregnancy can make the pregnancy much harder day-to-day. Fatigue from anaemia can be debilitating, compounding the normal tiredness of pregnancy.

Treating iron deficiency often markedly improves a pregnant woman’s energy levels and overall sense of well-being, which is important for her to care for herself and prepare for the new baby.

Testing iron status and when to consider supplements

How do you know if you should take an iron supplement? The answer is: test, don’t guess.

Research consistently shows that taking iron during pregnancy reduces the risk of anaemia and can improve birth outcomes.

Because of this, health authorities strongly recommend iron supplementation in pregnancy. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises that all pregnant women take a daily iron supplement (30–60 mg of elemental iron) along with folic acid, starting as early as possible, to prevent anaemia and reduce the risk of premature birth and low birth weight [8].

Many prenatal vitamins include around 30 mg of iron for this reason. In some European countries, doctors test ferritin or haemoglobin in early pregnancy and will prescribe iron pills if levels are low. In other cases, a prenatal multivitamin containing iron is given to all as a preventive measure.

Always discuss with a health care professional before starting any new supplement routines.

What are your iron requirements?

Recommended dietary iron intake [9]:

Women (non-pregnant, premenopausal): 15 mg/day

Pregnancy: 27–30 mg/day

Breastfeeding: 10–15 mg/day (lower than pregnancy due to absence of menstruation, but needs vary based on blood loss and iron stores)

Men, women (post-menopause): 9 mg/day

Some food authorties like EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) do not set a higher requirement for iron during pregnancy, because physiological adaptations (increased absorption, use of stores) theoretically cover part of the need. However, EFSA states that diet alone is often insufficient and that supplementation is commonly required in pregnancy, especially when iron stores are low at conception [10].

This is why, in practice, most clinical and public health guidance in Europe aligns with ~27–30 mg/day total intake, usually achieved via supplementation.

Where to find iron in your diet

While supplements can play a role, nutrition is the cornerstone of maintaining good iron status. A food-first approach means you prioritize getting iron from your diet, which brings along other beneficial nutrients and is less likely to cause excessive iron levels.

There are two forms of dietary iron: heme and non-heme iron. Understanding the difference will help you make the most of your diet:

Heme Iron

This form of iron is found in animal-based foods and is highly bioavailable (easily absorbed by the body).

Sources of heme iron include:

Red meat (beef, pork, lamb, venison)

Poultry (chicken, turkey)

Seafood (fish and shellfish)

Note: While organ meats like liver are extremely high in iron as well, pregnant women should only consume liver in small quantities due to vitamin A content.

Non-Heme Iron

This form is found in plant foods and fortified products. Non-heme iron is abundant in many foods but is less efficiently absorbed (often only 2–20% absorbed) [9].

Sources of non-heme iron include:

Legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans, soybeans/tofu)

Leafy green vegetables (spinach, kale, collard greens)

Whole grains and fortified cereals

Nuts and seeds (pumpkin seeds, cashews, hemp seeds)

Dried fruits (raisins, apricots, prunes)

For instance, spinach might contain 3 mg of iron per cooked cup, or a cup of cooked lentils about 6 mg, which is great, but due to inhibitors in those foods, the body may only absorb a small percentage.

Many breakfast cereals and breads are fortified with iron (read labels; some provide a large percentage of the daily iron requirement), and these can help, especially for vegetarians.

Non-heme iron absorption is heavily influenced by other dietary factors, which brings us to the next point…

Tips to improve dietary iron absorption

Pair iron foods with Vitamin C-rich foods

Vitamin C is a powerful enhancer of non-heme iron absorption [9]. Eating foods high in vitamin C along with your iron-rich plant foods can significantly increase the iron you absorb.

For example, add citrus fruits (lemons, oranges, grapefruit) or berries to a meal, include bell peppers, tomatoes, or broccoli with your iron-rich vegetables, or drink a bit of orange juice when you have your morning fortified cereal.

Even squeezing lemon juice over spinach or lentils, or adding tomato sauce to a bean stew, can help. This is an easy and tasty way to boost iron uptake.

Avoid inhibitors around mealtime

Certain common compounds can hinder iron absorption. The big ones are phytates (found in high-fibre foods like whole grains and legumes), polyphenols/tannins (found in tea, coffee, red wine, and some grains), and calcium (from dairy or supplements).

This doesn’t mean you should avoid healthy whole grains or legumes. Instead, consider preparation methods and timing:

Soaking, sprouting, or fermenting: If you eat a lot of legumes or whole grains, traditional prep methods like soaking beans overnight, sprouting grains, or using sourdough fermentation can break down phytates and improve iron availability.

Tea and coffee timing: Try not to drink tea or coffee with your iron-rich meal. It’s best to enjoy those beverages between meals. Even a couple hours before or after is fine. Studies show that tea or coffee can reduce iron absorption significantly if consumed together with an iron-rich food [9]. So, for example, have your morning latte after you’ve had your iron-fortified cereal, not alongside it.

Calcium separation: Calcium is a bit unique because it can inhibit both heme and non-heme iron absorption when taken together [9]. If you take a calcium supplement, take it at a different time of day than your iron supplement. And if you are eating an iron-rich dinner, maybe don’t have a big glass of milk with it; save dairy for another snack or meal. Small amounts of dairy in the meal won’t make a huge difference, but a calcium-heavy meal (like a cheesy cream sauce over a spinach dish) might interfere with iron. Balance it out by adding vitamin C or meat to that meal to counteract the effect, or by spacing things out.

Cook in cast iron cookware

Interestingly, cooking acidic or moist foods (like tomato sauce, chili, etc.) in cast iron pots or pans can leach a bit of iron into the food. This can increase the iron content of the meal modestly. This isn’t a primary strategy, but it’s a neat little bonus if you have cast iron cookware.

Include meat, fish or poultry in mixed meals

The presence of even a small amount of meat can help absorb iron from plant foods in the same meal [9]. So if you’re omnivorous, mixing plant and animal sources in one meal is beneficial.

Spread iron intake through the day

Your body can only absorb so much iron at once. If you eat all your daily iron in one huge serving, the absorption fraction may be lower than if you spread those iron-rich foods into a couple of meals.

Try to include some iron-containing food at each meal. For instance, an iron-fortified cereal or eggs in the morning, a spinach chickpea salad at lunch, and a portion of meat with beans or greens at dinner. Spacing it out also helps avoid overwhelming inhibitors at one meal.

Sources of dietary iron in more detail

Below is a quick reference list of iron-rich foods, divided by heme vs non-heme sources. Incorporating a variety of these into your weekly diet will go a long way to improving iron status:

Top Heme Iron Sources (Animal-based):

Lean Red Meat – Beef, lamb, pork (for example, 100g of beef contains ~2.5 mg iron, and it’s well absorbed).

Organ Meats – Liver, kidney (very high in iron, e.g. a slice of beef liver can provide over 5 mg iron but consume liver sparingly during pregnancy due to vitamin A).

Poultry – Chicken, turkey (dark meat contains more iron than white meat; 100g of dark turkey meat ~1.4 mg iron).

Fish and Seafood – e.g. Shellfish like clams, mussels, oysters (extremely rich in iron – 100g of clams can provide over 20 mg of iron, and oysters ~7 mg); also sardines, tuna, salmon (~1–2 mg per 100g).

Eggs – While technically not heme iron (eggs contain non-heme iron), they are an animal product often grouped here. One large egg has about 0.8 mg iron.

Top Non-Heme Iron Sources (Plant-based and fortified):

Legumes – Lentils (~6.6 mg per cup cooked), chickpeas (~4.7 mg per cup), black beans (~3.6 mg), kidney beans, soybeans and tofu (1/2 cup tofu ~3 mg).

Leafy Greens – Spinach (~3-4 mg per 1/2 cup cooked, though high in oxalates), swiss chard, kale, broccoli (1 cup cooked broccoli ~1 mg but with vitamin C inherent).

Whole Grains – Quinoa (~2.8 mg per cup cooked), amaranth, oatmeal (~2 mg per cup cooked), and fortified grains like breakfast cereals. Many cereals are fortified with 8–18 mg of iron per serving. Check labels; these can be very helpful, especially if paired with fruit for vitamin C.

Nuts and Seeds – Pumpkin seeds (~2.5 mg per 30g handful), cashews (~2 mg per handful), sesame seeds/tahini (~1.3 mg per tablespoon), flaxseeds, hemp seeds.

Dried Fruits – Raisins (~1.0 mg per small box), dried apricots (~2.7 mg per 1/2 cup), prunes (~1.6 mg per 1/2 cup). These can be good snacks or additions to trail mix, salads, or cereal.

Fortified Foods – Aside from cereals, foods like fortified plant-based milks, nutritional yeast, or even some breads can contain added iron.

Molasses – Blackstrap molasses is an old-fashioned remedy for iron; 1 tablespoon has about 3.5 mg of iron. It’s quite potent in flavour, but can be used in baking or stirred into oatmeal as a sweetener with an iron boost.

Final word on iron and fertility

Iron is not just about preventing anaemia; it underpins many processes vital to conception. Indeed, studies find that women struggling with unexplained infertility often have lower iron stores or outright iron deficiency [7]. Women with a history of recurrent miscarriage have also been found to have lower iron levels on average [7]. While iron is rarely the only factor in infertility, it’s a piece of the puzzle we don’t want to overlook. Optimising iron status can improve ovulation, support a healthy uterine lining and placenta, and ensure both partners have the energy and reproductive health needed for a successful pregnancy.

Emotional note: If you find out you are iron-deficient in pregnancy, try not to feel guilty or ashamed. The majority of pregnant women end up needing extra iron; it’s not a personal failing, but rather biology. With proper support (dietary changes and supplements as needed), you can restore your iron levels. Healthcare providers are very accustomed to managing this, so don’t hesitate to discuss testing and options.

References

[1] Global Nutrition Report | Country Nutrition Profiles - Global Nutrition Report. (n.d.). https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/europe/western-europe/belgium/

[2] TRADING ECONOMICS. (n.d.). Belgium - Prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age (% of women ages 15-49) - 2026 data 2027 forecast 1990-2023 historical. https://tradingeconomics.com/belgium/prevalence-of-anemia-among-women-of-reproductive-age-percent-of-women-ages-15-49-wb-data.html

[3] Milman, N., Taylor, C. L., Merkel, J., & Brannon, P. M. (2017). Iron status in pregnant women and women of reproductive age in Europe. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 106(Suppl 6), 1655S–1662S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.156000

[4] McCarthy, E. K., Schneck, D., Basu, S., Xenopoulos-Oddsson, A., McCarthy, F. P., Kiely, M. E., & Georgieff, M. K. (2024). Longitudinal evaluation of iron status during pregnancy: a prospective cohort study in a high-resource setting. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 120(5), 1259–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2024.08.010

[5] Chavarro, J. E., Rich-Edwards, J. W., Rosner, B. A., & Willett, W. C. (2006). Iron intake and risk of ovulatory infertility. Obstetrics and gynecology, 108(5), 1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000238333.37423.ab

[6] Obeagu EI, Afolabi BA. The Impact of Maternal Anemia on Placental Development and Function: A Review. Lifeline Health Sciences, 2025; 3(1): 1-12

[7] Guo, L., Yin, S., Wei, H., & Peng, J. (2024). No evidence of genetic causation between iron and infertility: a Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1390618. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1390618

[8] https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/daily-iron-pregnancy

[9] Office of Dietary Supplements - Iron. (2025). https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-HealthProfessional/

[10] EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. (2015). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for iron. EFSA Journal, 13(10), 4254. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4254